Wyndham

Wyndham Fisher

Fisher Ghosts of Culloden Moor 21 - MacLeod (Cathy MacRae)

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 21 - MacLeod (Cathy MacRae) Ghosts of Culloden Moor 06 - Fraser

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 06 - Fraser Ghosts of Culloden Moor 18 - Watson

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 18 - Watson Scottish Snow & Mistletoe: A Short Story

Scottish Snow & Mistletoe: A Short Story Dougal

Dougal The Curse of Clan Ross

The Curse of Clan Ross Moodie

Moodie Be Witched

Be Witched Ghosts of Culloden Moor 04 - Payton

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 04 - Payton Ghosts of Culloden Moor 27 - Finlay

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 27 - Finlay Connor

Connor Christmas Kiss (A Holiday Romance) (Kisses and Carriages)

Christmas Kiss (A Holiday Romance) (Kisses and Carriages) A Good Day for Crazy: A Time Travel Mystery

A Good Day for Crazy: A Time Travel Mystery Ghosts of Culloden Moor 08 - Duncan

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 08 - Duncan Ghosts of Culloden Moor 26 - Patrick (Cathy MacRae)

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 26 - Patrick (Cathy MacRae) Going Back for Romeo

Going Back for Romeo Payton

Payton Ghosts of Culloden Moor 02 - Lachlan

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 02 - Lachlan Kiss This

Kiss This Ghosts of Culloden Moor 15 - Gerard

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 15 - Gerard Watson

Watson Jamie

Jamie Ghosts of Culloden Moor 20 - Connor

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 20 - Connor Kilt Trip: (Scottish Historical Romance) (Scavenger Hunting Book 1)

Kilt Trip: (Scottish Historical Romance) (Scavenger Hunting Book 1) Ghosts of Culloden Moor 11 - Adam

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 11 - Adam Ghosts of Culloden Moor 19 - Iain (Melissa Mayhue)

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 19 - Iain (Melissa Mayhue) Ghosts of Culloden Moor 01 - The Gathering

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 01 - The Gathering Finlay

Finlay Ghosts of Culloden Moor 05 - Gareth

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 05 - Gareth Collecting Isobelle

Collecting Isobelle Percy

Percy![[Highlander Time Travel 01.0 - 03.0] The Curse of Clan Ross Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/30/highlander_time_travel_01_0_-_03_0_the_curse_of_clan_ross_preview.jpg) [Highlander Time Travel 01.0 - 03.0] The Curse of Clan Ross

[Highlander Time Travel 01.0 - 03.0] The Curse of Clan Ross Under the Kissing Tree

Under the Kissing Tree Unraveling James

Unraveling James Rabby

Rabby Bram--#35--Ghosts of Culloden Moor

Bram--#35--Ghosts of Culloden Moor Kilt Trip

Kilt Trip Ghosts of Culloden Moor 10 - Macbeth

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 10 - Macbeth Pirate Trip: (Historical Romance) (Scavenger Hunting Book 2)

Pirate Trip: (Historical Romance) (Scavenger Hunting Book 2) Ghosts of Culloden Moor 23 - Brodrick

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 23 - Brodrick Gone Duck

Gone Duck Lord Fool to the Rescue

Lord Fool to the Rescue Ghosts of Culloden Moor 30 - MacBean (Darcy)

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 30 - MacBean (Darcy) James

James Ghosts of Culloden Moor 22 - Murdoch (Diane Darcy)

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 22 - Murdoch (Diane Darcy) Tristan

Tristan Brodrick

Brodrick The Blacksmith: A Highlander Romance (The Ghosts of Culloden Moor Book 38)

The Blacksmith: A Highlander Romance (The Ghosts of Culloden Moor Book 38) Not Without Juliet (A Scottish Time Travel Romance) (Muir Witch Project #2)

Not Without Juliet (A Scottish Time Travel Romance) (Muir Witch Project #2) Lachlan

Lachlan The Lad That Time Forgot

The Lad That Time Forgot Ghosts of Culloden Moor 03 - Jamie

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 03 - Jamie Ghosts of Culloden Moor 12 - Dougal

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 12 - Dougal Ghosts of Culloden Moor 07 - Rabby

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 07 - Rabby Tristan: A Highlander Romance (The Ghosts of Culloden Moor Book 31)

Tristan: A Highlander Romance (The Ghosts of Culloden Moor Book 31) Rhys: A Highlander Short

Rhys: A Highlander Short Ghosts of Culloden Moor 29 - Rory (Jones)

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 29 - Rory (Jones) Ghosts of Culloden Moor 16 - Malcolm (Cathy MacRae)

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 16 - Malcolm (Cathy MacRae) Somewhere Over the Freaking Rainbow (A Young Adult Paranormal Romance) (The Secrets of Somerled)

Somewhere Over the Freaking Rainbow (A Young Adult Paranormal Romance) (The Secrets of Somerled) Ghosts of Culloden Moor 24 - The Bugler

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 24 - The Bugler Hamish

Hamish Jack

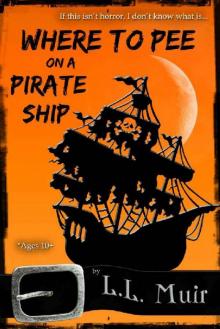

Jack Where to Pee on a Pirate Ship

Where to Pee on a Pirate Ship Gerard

Gerard Ghosts of Culloden Moor 09 - Aiden

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 09 - Aiden The Bugler

The Bugler Ghosts of Culloden Moor 28 - Hamish

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 28 - Hamish Freaking Off the Grid

Freaking Off the Grid![Rory [Jones] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/13/rory_jones_preview.jpg) Rory [Jones]

Rory [Jones] Ghosts of Culloden Moor 14 - Liam (Diane Darcy)

Ghosts of Culloden Moor 14 - Liam (Diane Darcy)